Something a little

different this time, a sojourn based on one of Holmes’ contemporaries, but on

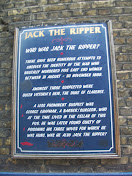

the other side of the law. Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in the

largely impoverished areas in and

around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. In both

the criminal case files and contemporary journalistic accounts, the killer was

called the Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron.

Watson’s originally

published accounts make no mention of Holmes having any involvement in the search

for the Ripper, but subsequent discoveries of alleged Watsonian manuscripts

have given multiple accounts of the most famous Victorian detective and most

famous Victorian serial killer crossing swords (or knives). Two excellent films

‘A Study in Terror’ and ‘Murder By Decree’ have also dramatised other

accounts, with several computer games focusing around the match-up.

Even Watson’s

literary agent, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in an interview with an American

journalist republished in ‘The Portsmouth Evening

News’ on 4th July 1894., explained

how Holmes would have set about the work of tracking the Ripper by deducing the

writer of the ‘Dear Boss’ letter. Also, the historical record, as we shall see,

gives a hint that the Great Detective may have had some involvement in the

ending of Jack’s reign of terror.

Travelling

up to Tower Hill, listening to an audiobook of the excellent ‘The

Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper’

(by Hallie Rubenhold), read by Louise Brealey

(Molly Hooper in ‘Sherlock’), I then made my way to my first port of

call – ‘The Jack the Ripper Museum’,

situated

in a historic Victorian house in Cable Street in the heart of Whitechapel. The

museum, which was controversial when it opened, tells the full story of the

Jack the Ripper murders, focusing on the lives of the victims, the main

suspects in the murders, the police investigation and the daily life of those

living in the east end of London in 1888. Six floors

recreate the murder scene in Mitre Square, Jack's sitting room, the Whitechapel

police station, victim Mary Jane Kelly's bedroom, and the mortuary. I found an appropriate focus on the victims, and along with 'The Five' came away with a better idea of the five canonical victims, only one of which it can be proved was a prostitute. I also had not realised that the victims had almost certainly been attacked whilst sleeping rough (save the final victim who was in her own bed) hence the lack of defensive wounds.

A short walk brought me to ‘Happy Days’, a Fish and Chips

restaurant on Goulston Street. After

the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes in the early morning

hours of 30 September 1888, police searched the area near the crime scenes in

an effort to locate a suspect, witnesses or evidence. At about 2.55am,

Constable Alfred Long of the Metropolitan Police Force discovered a piece of an

apron in the stairwell of a tenement, 108-119 Goulston Street, Whitechapel. The

cloth was stained with blood and faeces, and the blade of a knife had evidently

been wiped on it. On the arrival of another officer on the scene, Long took the

portion of apron round to Commercial Street Police Station, where he handed it

to an Inspector. The piece of cloth was later confirmed as being the missing

part of the apron worn by Catherine Eddowes. Above where the apron piece was

found (which is now part of ‘Happy Days’), there was writing in white chalk on

either the wall or the black brick jamb of the entranceway – “The Juwes are the men that will not be

blamed for nothing”. This message plays an important part in the film ‘Murder

by Decree’.

A five minute walk took me to Gunthorpe Street. On 7th

August 1888, a little after 5am, the body of Martha Tabram was found on the

first floor landing of a tenement building in George Yard, a dark and sinister

alley. Tabram had suffered a frenzied assault, and 39 stab wounds had been

inflicted from her throat to her lower abdomen. A friend of Tabram, and a

fellow prostitute, Mary Anne Connelly, told police that she and Tabram had

spent the previous evening drinking with two soldiers along Whitechapel Road.

Just before midnight they had split into couples and Tabram had led her soldier

through an arch into Gunthorpe Street which leads to George Yard, whilst she

had gone into an adjourning alley. The soldier was never identified, and

because her injuries were not consistent with those of the latter victims – she

had been stabbed rather than ripped – Tabram’s murder is generally ruled out as

being the work of the Ripper.

However, the

nearby ‘White Hart’ public house also

has a possible Ripper link. On 13th February 1894, the Sun newspaper began a series of articles

in which it claimed to know the Ripper’s identity. Although they never named

their suspect, it was clear that they were referring to Thomas Hayne Cutbush,

the nephew of a senior Metropolitan Police Officer. Worried that they may be

accused of a cover-up, the Chief Constable of Scotland Yard, Sir Melville

Leslie Macnaghten, was asked to prepare a document in which he refuted the Sun’s claims. This document, now known

as the Macnaghten Memorandum, was rediscovered in the late 1950s, and was found

to mention the names of three suspects “any

one of whom would have been more likely than Cutbush”. The first of these

names was George Chapman, born Severin Klosowki in Poland. In 1887 having

qualified as a junior surgeon, Chapman came to London, finding work as an

assistant hairdresser. In October 1889, he married Lucy Baderski, and by 1890

was working as a barber in the basement of the ‘White Hart’. A board on the side of the public house emphasises

its Ripper connection. It is also the starting point for a nightly ‘Jack The

Ripper Tour’.

Walking to my next stop, I passed a barbers with a punning

name – Jack The

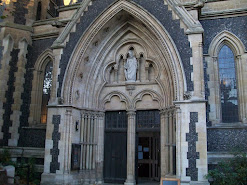

Clipper - finally reaching the soaring white tower of Christchurch,

Spitalfields, which dominates its

surroundings today just as it did in 1888 when the Ripper’s victims would have

glanced on it on an almost daily basis, as they pounded the streets trying to earn money to be put up in a common lodging house.

Opposite was the ‘Ten Bells’ public house, linked with the final hours of both Annie

Chapman and Mary Kelly. Chapman may have drunk at the pub shortly before she

was murdered; and it has been suggested that the pavement outside of the pub

was where Kelly picked up clients as a prostitute. Between 1976 and

1988, the public house was named ‘The

Jack the Ripper’, and memorabilia relating to the case were displayed in

the bars. The brewery ordered the change back to its original name after a long

campaign by ‘Reclaim the Night’ demanded that a murderer of women should not be

commemorated in such a fashion. It also appeared in the Johnny Depp Ripper-film 'From Hell', including a scene

showing Depp (as Inspector Abberline) having a drink with Ripper victim Mary

Kelly (Heather Graham). A car park now occupies the site of Dorset Street where

Mary Kelly was murdered on 9th November 1888.

A short walk brought me to the rather ugly brewery building which

now stands on the site of 29 Hanbury Street, in the back yard of which the body

of Annie Chapman was found at 6am on 8th September 1888. However, the

opposite section of Hanbury Street, the south side, is more or less intact, so

it is possible at least to gain an impression of what the north side would have

looked like at the time of the murder. On the evening of 7th

September 1888, Chapman arrived at her lodging house in Dorset Street

intoxicated. Not having the money for her bed, he was escorted off the

premises. Chapman pleaded with the manager to stay, but he observed that she

could find money for beer but not a beer. At 5.30am on the 8th, a

Mrs Elizabeth Long, noticed Chapman talking to a man outside 29 Hanbury Street.

She found nothing suspicious about their behaviour and hurried by. However, she

noted that the man who had his back to her wore a deerstalker, and had a 'shabby genteel'

appearance. Was this Holmes following a lead that Chapman was to be the next

victim ? However, Long also stated that

the man that she saw seemed to be a foreigner.

Another short walk took me to Brick Lane, and the Brick

Lane Hotel, which was formerly the ‘Frying Pan’ public house, it was here that Mary Nichols (known as

Polly), the first ‘canonical’ Ripper victim, drank away her doss money on the

night of her murder, 30th August 1888. Her inquest revealed that she

had been turned out of the Thrawl Common Lodging House because she did not have

the money (four pence) to pay for her bed. She was last seen alive at 2.30am,

when she met her friend Ellen Holland at the junction of Osborn Street and

Whitechapel Road. Nichols told Holland that she had made her doss money twice

over, seemingly from prostitution, but that she had drunk it all away in the ‘Frying Pan’. Close scrutiny of the

building’s upper storeys reveals that two crossed frying pans still adorn its

upper gable, along with its original name ‘Ye

Frying Pan’. Holland had tried to persuade Nichols to come back to the lodging

house, but she refused, and instead headed unsteadily off along Whitechapel

Road.

Continuing along Whitechapel Road, I finally reached The

Royal London Hospital, where a Dr. Thomas Openshaw worked as a

pathologist. His opinion was sought in connection with the “From Hell” letter in October 1888.

This was a letter sent alongside half a preserved human kidney to the

chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, George Lusk. The author of the

letter claimed to be the Ripper, and to have fried and eaten the other half of

the kidney. It was also here that Emma Smith, the first Whitechapel Murders

victim died. In the early hours of 3rd April 1888, she was assaulted

and robbed by a gang of three men on Brick Lane. She survived the first attack,

but died in hospital the next day of peritonitis. At the subsequent inquest, a

verdict of “wilful murder by some person,

or persons, unknown” was returned. However, it is almost certain that Smith

was not murdered by the Ripper, given the lack of mutilation. She was probably

the victim of one of the street gangs that were known to prey on the vulnerable

prostitutes of the area.

Making my way to

Whitechapel Underground Station, I caught a tube to Cannon Street, for a brief respite

from the Ripper, having a quick lunch and visiting sites from ‘The Man With

The Twisted Lip'. First port of call was Upper Thames Street, the location of ‘The Bar of Gold’, the Opium

Den in which Neville St. Clair was last seen alive, and where Watson found a

disguised Holmes.

The nearby ‘Bennett’s Hill’, was the true name

of ‘Fresno Street’, where Mrs. St. Clair was walking when she saw her husband

in an upper window.

It was then time to return to

Jack the Ripper, by visiting locations used in the 1979 ‘Holmes vs the Ripper’

film, ‘Murder by Decree’. After around

a fifteen minute walk (and crossing the Thames via the Millennium Bridge seen

in ‘Sherlock: A Scandal in Belgravia’, and passing Borough Market which appears in 'Sherlock: The Six Thatchers'), I found myself in Clink

Street (a location used in multiple films and in the Sherlockian Doctor Who

story ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’).

Scenes featuring Holmes (Christopher Plummer) searching for Mary Kelly (Edina Ronay) and both

of them being pursued by a carriage, with Holmes being knocked down and Mary

kidnapped. Clink Street also contains one of England’s oldest and

most notorious prisons, The Clink (from which other prisons are named), which dates

back to 1144. It is now a Prison Museum.

Making my way to

the nearby London Bridge Underground Station, I caught a tube to Green Park. A

short walk took me to the Royal Academy of Arts (Burlington House), which

appears in the film’s opening as the Royal Opera House, from which Holmes and

Watson (James Mason) are returning to Baker Street. (Barton Street, visited

in a previous Sojourn)

A fifteen minute

walk brought me to Carlton Gardens, where a

scene where medium Robert Lees (Donald Sutherland) points the home

of the killer out to Inspector Foxborough (David Hemmings), was filmed.

A ten minute walk brought me to Charing Cross Station, where Holmes and Watson catch trains in ‘The Abbey

Grange’ and ‘The Golden

Pince-Nez’, and where Watson learns that Holmes has been hospitalised in ‘The

Illustrious Client’. I then caught the Northern Line back to Morden, and

then a bus home, continuing to listen to ‘The Five’.