Having spent the morning walking around sites from Agatha Christie and ‘Midsomer Murders’, my afternoon was to be spent in Oxford, a location most associated with another fictional detective, Chief Inspector Endeavour Morse (whose locations I will also highlight), but which may feature in the Sherlock Holmes canon also, as it not clear from Watson’s depiction of the university town of ‘Camford’, whether Professor Presbury worked in Cambridge or Oxford. Holmes may also have attended Oxford University himself, making friends with Victor Trevor and Reginald Musgrave.

It was, however, Oxford where Father Ronald Knox was a fellow. In 1928, Knox published ‘Essays in Satire’ which included ‘Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes’, the first of the genre of mock-serious critical writings on Sherlock Holmes and mock-historical studies in which the existence of Holmes, Watson, et al. is assumed, now referred to as ‘the game’. He had previously, along with his three brothers, sent a letter to Arthur Conan Doyle in 1904, highlighting inconsistencies in the ‘Sherlock Holmes’ stories. He is also known for his ‘Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction’ that describe a philosophy of writing in which the reader can participate, attempting to find a solution to the mystery before the fictional detective reveals it.

Alighting from my bus on the High Street, it was a short walk to my first stop, The Chequers Inn, a fifteenth-century building which became a tavern in c1500. This inn would seem to confirm that the visit to Professor Prestbury in ‘The Creeping Man’ was to Oxford, as Cambridge does not have an inn named ‘The Chequers’.

“Tomorrow, Mr. Bennett, will certainly see us in Camford. There is, if I remember right, an inn called the Chequers where the port used to be above mediocrity and the linen was above reproach. I think, Watson, that our lot for the next few days might lie in less pleasant places” – Holmes [CREE]

It was then a short walk to my first Oxford College of the afternoon, St. John’s College which was identified by Roger Lancelyn Green as being ‘St Luke’s’ in ‘The Three Students’, where a tutor, Mr. Hilton Soames, had been reviewing the galley proofs of an exam he was going to give when he left his office for an hour. When he returned, he found that his servant had accidentally left his key in the lock, and someone had disturbed the exam papers on his desk leaving the three students who will take the exam live above him in the same building as the main suspects.

_College_1%20%5B3STUD%5D.JPG)

_College_2%20%5B3STUD%5D.JPG)

_College_3%20%5B3STUD%5D.JPG)

_College_4%20%5B3STUD%5D.JPG)

“The sitting-room of our client opened by a long, low, latticed window on to the ancient lichen-tinted court of the old college. A Gothic arched door led to a worn stone staircase. On the ground floor was the tutor's room. Above were three students, one on each storey” – Watson [3 STUD]

The recently departed Nicholas Utechin also chose this college as Holmes’ on the basis that an Edmund Gore Alexander Holmes went up there in 1869 on a scholarship, a George Musgrave and a John Escott (Holmes’ pseudonym in ‘Charles Augustus Milverton’) also attended the college at the relevant times. This would also explain the otherwise mysterious comment in ‘The Three Students’ that Holmes knew the door structure in the college. St John's is the wealthiest college in Oxford, with a financial endowment of £600 million as of 2020, largely due to nineteenth-century suburban development of land in the city of Oxford of which it is the ground landlord. St. John’s is also Morse’s college in the book, ‘The Riddle of the Third Mile’.

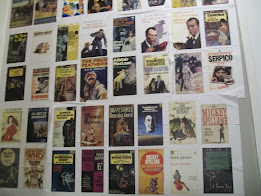

Retracing my steps, I passed the Randolph Hotel, which appears in ‘Inspector Morse’ TV episodes ‘The Wolvercote Tongue’, ‘The Infernal Serpent’, ‘Second Time Around’, ‘The Wench is Dead’, and ‘The Remorseful Day’. Next, I popped into a bookshop, ‘Book Stop’, which had wallpaper on the stairs down to the basement featuring three ‘Sherlock Holmes’ book covers (along bizarrely with the cover to the novelisation of 'Doctor Who' story ‘Full Circle’).

Back on the street, another short walk brought me to Trinity College, where in 1910, Father Ronald Knox became a fellow. The college was founded in 1555 by Sir Thomas Pope, on land previously occupied by Durham College, home to Benedictine monks from Durham Cathedral. It was founded as a men's college and has been coeducational since 1979. Trinity has produced three British prime ministers (William Pitt the Elder, Lord North & Spencer Compton), placing it third after Christ Church and Balliol in terms of former students who have held the office. Knox’s room, No. 84 was located on the ground floor on the right side of the Garden Quad. Unfortunately, due to building work taking place there was no access to the College, and I had to make do with photos taken through protective fencing. Trinity College also appears in Morse episodes ‘The Last Enemy’, ‘The Wench is Dead’ and ‘Twilight of the Gods’.

Opposite the College was Turl Street, a possible location for Holmes and Watson’s hansom cab ride to meet Professor Prestbury in ‘The Creeping Man’. Turl Street also appeared in ‘Deadly Slumber’.

“A friendly native on the back of a smart hansom swept us past a row of ancient colleges and, finally turning into a tree-lined drive, pulled up at the door of a charming house, girt round with lawns and covered with purple wisteria” - Watson [CREE]

One of these ‘ancient colleges’ is Exeter College, the fourth-oldest college of the University, where in both print and television, Morse collapsed in the front quad with a heart attack in ‘The Remorseful Day’. The College was founded in 1314 by Devon-born Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, as a school to educate clergymen. It is also the alma mater of my own father, and of Philip Pullman whose play ‘Sherlock Holmes and the Adventure of the Sumatran Devil’ (later renamed 'Sherlock Holmes and the Limehouse Horror') was partially responsible for my interest in Holmes. (Pullman renamed Exeter as ‘Jordan College’ in his ‘His Dark Materials’ books). Other Exeter College alumni include J. R. R. Tolkien, Richard Burton, Roger Bannister, and Alan Bennett.

A little way further on was Brasenose College, which began as Brasenose Hall in the thirteenth-century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mid-17th century and the new quadrangle in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The exterior of Brasenose acted as the exterior of ‘Brompton School’ in ‘Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear’ (1985). It also appears several times in ‘Inspector Morse’, including as the fictional ‘Beaumont College’ in ‘The Last Enemy’.

_1%20%20%5BYoung%20Sherlock%20Holmes%201985%5D.JPG)

_2%20%20%5BYoung%20Sherlock%20Holmes%201985%5D.JPG)

_3%20%20%5BYoung%20Sherlock%20Holmes%201985%5D.JPG)

_4%20%20%5BYoung%20Sherlock%20Holmes%201985%5D.JPG)

A short distance away was Merton College. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor to Henry III and later to Edward I, first drew up statutes for an independent academic community and established endowments to support it. An important feature of de Merton's foundation was that this "college" was to be self-governing and the endowments were directly vested in the Warden and Fellows. It was at Merton College that the first reading of Father Knox’s paper, then entitled ‘The Mind and Art of Sherlock Holmes’, is thought to have taken place, on Friday 10th March 1911, in the room of Reginald Diggle, a member of the college’s Bodley Club. It also appears in ‘The Service of All The Dead’ and ‘The Infernal Serpent’. The College was just closing to visitors, so again I had to take some photos through the doorway.

My final University College of the day was the impressive Christ Church College. This was founded in 1546, one of the most prestigious colleges with 13 British Prime Ministers (including Gladstone), philosophers (eg. John Locke), reformers (eg. John Wesley) and scientists (eg. Robert Hooke) amongst its alumni. It is also the only Oxbridge college to also be a cathedral.

In his seminal essay, Knox stated that he believed Holmes attended Christ Church. He seems to have named Christ Church due to its prestige, elitism and wealthy clientele which he stated explained Holmes’ isolationism when at university. Roger Lancelyn Green stated Holmes left Cambridge after two years and embarked on a new course of study at Christ Church Oxford. He quotes both a Holmes (R E H Holmes) and a Musgrave as being at Christ Church. Unfortunately, entry tickets for the College had sold out, so again it was photos through a doorway. Christ Church features in ‘Twilight of the Gods’ and ‘The Daughters of Cain’, as well as in the first two ‘Harry Potter’ films as part of Hogwarts.

It was then time for a final visit, outside the City Centre, catching a bus from a nearby bus stop to Radley College, an independent boarding school for boys, near Radley, Oxfordshire, which was founded in 1847. Radley is one of only three public schools to have retained the boys-only, boarding-only tradition, the others being Harrow and Eton). Old Radleians include (comedy Sherlock) Peter Cook, Desmond Llewellyn (James Bond’s Q, and guest star in two Clive Merrison dramatisations, ironically including ‘The Three Students’), and (Sherlockian author) James Lovegrove. However, it was for its brief starring role as one of the quads of ‘Brompton School’ (along with Eton College) in ‘Young Sherlock Holmes’ that I wished to visit it.

I had initially believed that I would be able to get photos through railings or a doorway, but on arrival it became clear that the College was at the end of a very long drive and comprised several buildings. However, several others got off my bus at the same stop and began walking confidently up the drive, so I joined them. On arrival at the main campus it became clear that the College was hosting ‘The European Transplant & Dialysis Sports Games 2022’, meaning that I was able to move freely without challenge. I was aware that the part of the campus that I needed was just next to the College Chapel, so following useful signs, after around ten minutes I found the required quad, which was where Elizabeth (Sophie Ward) was filmed chasing her dog.

_1%20%20%5BYoung%20Sherlock%20Holmes%201985%5D.JPG)

_3%20%20%5BYoung%20Sherlock%20Holmes%201985%5D.JPG)

Photos taken and I was back at the bus stop opposite the one where I alighted with time to spare to catch my bus back into central Oxford. I then slowly made my way to the railway station, passing the Oxford Castle and Prison (featured in ‘The Way Through The Woods’ and ‘The Wench is Dead’). On arrival at the Station, I took several photos as it appears in nine ‘Inspector Morse’ episodes (almost the most used location).

Settling back on the train home, passing the crowds at the Reading Festival, I mused on a very busy and very successful day.