Introduction

Having made two previous trips to Devon and Dartmoor, I decided to visit some sites that I had previously missed, relating to the novel and several individuals to which Conan Doyle owed a debt to varying degrees – namely Bertram Fletcher Robinson, George Newnes, Harry Baskerville, and George Turnavine Budd. As outlined in a previous post, I have watched/listened to over fifty dramatisations of HOUND, and in tribute to two of my favourites (09 Lives & British Touring Shakespeare), I found myself visiting several graveyards.

In preparing this sojourn I was indebted to 'Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes & Devon: A Complete Tour & Companion', written by Brian W. Pugh, Paul Spiring, and S. Bhanji, and published by MX Publishing.

Day 1: Newton Abbot/Plymouth

‘Our friends had already secured a first-class carriage and were waiting for us upon the platform’ [HOUN – Chapter 6].

My journey started, as did Watson, Sir Henry and Dr. Mortimer’s did, at Paddington station, but instead of the reasonable time of 10.30am, my train was at 8.05am. After a two-and-a-half hour journey, I found myself at Newton Abbot Railway Station, which was opened on Wednesday 30th December 1846 by South Devon Railway Company. It was here on 23rd August 1902 that Conan Doyle met up with Jean Leckie (later his second wife) with the intention of showing her some of the ‘Baskerville Moor Country’, and was also where the body of Conan Doyle’s friend Bertram Fletcher Robinson was taken to from London Paddington on 24th January 1907 prior to his funeral. It is also likely that Conan Doyle began a journey to Sherborne from here on 3rd June 1901, having spent the previous night with Fletcher Robinson in nearby Ipplepen.

I was just in time for a bus into the centre, where I caught a bus into Ipplepen, and my second port of call, Park Hill House, the house to which Fletcher Robinson and his family moved in 1882. On Sunday 2nd June 1901, as part of their research trip, Conan Doyle and Fletcher Robinson visited Ipplepen to see the latter’s parents (referred to in a letter from Conan Doyle to his mother), and although it is not known for certain if they visited Park Hill House together, the coach house used to garage the vehicle in which they travelled is now called Park Hill Lodge, and is situated two doors to the left of Park Hill House, alongside Moor Road. The lintel of the carriage house doors can still be seen above the two newer windows. Fletcher Robinson’s parents died in 1903 and 1906, and he then owned the property himself between July 1906 and January 1907.

Continuing along the

road, and turning right, after around 10 minutes, I reached Honeysuckle

Cottage, where Henry Matthews Baskerville who was employed by the Fletcher

Robinsons as a ‘domestic’ at Park Hill House, lived. By the time of Conan

Doyle’s research trip in 1901, Henry was the ‘Head Coachman’ and was

responsible for one ‘Assistant Coachman’, three coaches and two horses. It was

he who drove his master’s son and Conan Doyle around the moor. Henry worked for

the Robinson family for about twenty years until 1905. (see Part Two)

A short distance further on, should have been a bench and plaque dedicated to the memory of Bertram Fletcher Robinson, highlighting his connection to ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’. However, despite looking for almost twenty minutes, I couldn’t find it.

Only a short distance further on was St. Andrew’s Church, in whose graveyard Bertram Fletcher Robinson is buried, as are his parents (Graveyard #1 of the week). The church also features two stained-glass windows dedicated to the Robinson family, both designed by the Victorian artist C.E. Kemp, who also produced windows for York Minster. The southern window in commemoration of Joseph Fletcher Robinson was commissioned by his widow, Emily, in 1903. The northern window was commissioned by Bertram in commemoration of his mother in 1906, and when he died six months later, his name was added to the inscription.

Having grabbed some lunch from a local shop, I then caught a bus back to Newton Abbot, where I was in plenty of time for my train to Plymouth, my base for the next few days. The journey was supposed to take 40 minutes, but due to points failure it was twice as long before I was arriving at the station where in May 1882, Conan Doyle arrived to set up in practice with a friend from university, George Turnavine Budd. He was greeted by an exuberant Budd in an impressive horse-drawn carriage.

My next port of call was

to have been another cemetery, Ford Park Road Cemetery, which houses the

grave of George Turnavine Budd, and his only son, William, but I decided to hold this over to the next day given that I had lost almost an hour of light.

Checking into my accommodation on the way, I made my way into central Plymouth, and Durnford Street, where Budd opened his surgery. The site of the surgery was demolished during 1958, initially being made into a car dealership called Renwick’s Garage, then into a luxury apartment block called Evolution Cove. Until 2003 the former site of the surgery was marked by a commemorative plaque. A series of twenty-two other plaques featuring quotes from the Sherlock Holmes canon can still be seen set within the footpath between 85 and 125 Durnford Street. An additional plaque is mounted within the lower step of 93 Durnford Street, but contains a number of errors – ‘A Study in Scarlet’ is called ‘A Study of Scarlet’, the number of stories is set at 68 rather than 60, and his time in Plymouth did not act as an inspiration for ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’.

Next up was 6 Elliot Terrace, part of a row of seven imposing six-storey Victorian mansions, constructed in around 1873 by Messrs Call & Pethick. The name derives from one Colonel James Elliot who once owned most of the land upon which Plymouth Hoe now stands. Conan Doyle resided with Budd and his family at 6 Elliot Terrace following his arrival in Plymouth in early May 1882. Records indicate that Budd co-leased the property with the Royal Western Yacht Club and the nearby Grand Hotel (where Conan Doyle stayed in February 1923). There is now a commemorative plaque on the address.

Returning to my accommodation, I settled in for the night, having a strenuous day planned for the next day.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Day 2: ‘The Moor’

‘But down beneath me in a cleft of the hills there was a circle of the old stone huts, and in the middle of them there was one which retained sufficient roof to act as a screen against the weather. My heart leaped within me as I saw it. This must be the burrow where the stranger lurked’.

[HOUN – Chapter 11]

Day two was my day on the moor. But first, I managed to make up for missing Budd’s grave the previous day, by attending as soon as it opened at 9am (Graveyard #2). Conan Doyle and Budd were classmates at Edinburgh and both rugby players (Budd playing for Blackheath as Watson had done). After graduating from the medical programme, Budd initially established a practice in Bristol. However, the cost of his plush lifestyle exceeded his income, leading to his moving moved to Plymouth, where things seemed to turn around for him. In May of 1882 he sent word to Conan Doyle asking him to come and join the practice. Despite being advised by all whose advice he sought not to join Budd’s practice, he did so anyway. When the partnership was about two months old Budd told Conan Doyle there was a problem. Profits had fallen and there wasn’t really room for two doctors in the practice. Later Doyle found out that Budd had found one of his mother’s disapproving letters about him and was upset by it.

Conan Doyle used Budd as the model for Dr. James Cullingworth in 'The Stark Munro Letters', and combined with their shared Edinburgh professor, Professor William Rutherford, as a part model for his most famous non-Sherlockian character, Professor George Challenger.

Making my way back to Plymouth Station, I caught the Dartmoor Explorer to ‘The Warren House Inn’ in Postbridge, one of the highest and most remote pubs in England. The first inn on the site is thought to date from around 1760 and stood on the opposite side of the road to the present ‘house’ and was known as the ‘New House’. That inn would have provided shelter and sustenance for miners and for travellers on the 1772 Morehamptonstead turnpike road, as did the replacement Warren House Inn (once called the Moreton Inn) in later years.

Even if Conan Doyle’s party did not then stop at the Warren House Inn, having been picked up by Fletcher Robinson’s coachman, Harry Baskerville, it certainly would have been visible to them across the valley. The landlord still guarantees a warm welcome today, declaring that the fire in the bar has been burning continuously since 1845 !

I then undertook part of a self-guided walk, ‘Tors and Tin’ planned by the Royal Geographic Society. Finding the starting point, I was soon walking across the moor, reaching a good example of a traditional Devon clapper bridge made from granite slabs taken from the surrounding landscape.

Continuing on, past locations used in the 'Doctor Who' story, 'The Sontaran Experiment', I found myself at Grimspound, a late Bronze Age settlement. The Anglo Saxons knew ‘Grim’ as the Devil, and it is a prefix to placenames associated with evil legends throughout England. It also inspired the name ‘Grimpen’ in ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’.

Reminiscing about his trip around Dartmoor with Conan Doyle, Fletcher Robinson recalled:

‘We tramped eastward to the stone fort of Grimspound, which the savages of the Stone Age…raised with enormous labour to act as a haven of refuge from marauding tribes. The twenty feet slabs of granite – how they were ever hauled to their places is a mystery – still encircle the stone huts where the tribe lived. Into one of these Doyle and I walked….It was one of the loneliest spots in Great Britain. Strange legends of lights and figures are told concerning it.’

It was in a stone hut similar to those in Grimspound that Watson discovered the hiding place of an incognito Holmes:

‘Far away came the sharp clink of a boot striking upon a stone. Then another and yet another, coming nearer and nearer. I shrank back into the darkest corner and cocked the pistol in my pocket, determined not to discover myself until I had an opportunity of seeing something of the stranger. There was a long pause which showed that he had stopped. Then once more the footsteps approached and a shadow fell across the opening of the hut.

“It is a lovely evening, my dear Watson,” said a well-known voice. “I really think that you will be more comfortable outside than in”.’ - Chapter 11 [HOUN]

Retracing my steps I returned to the Warren House Inn, for some liquid refreshment prior to catching the Dartmoor Express, making my way to Princetown, from where Conan Doyle wrote to his mother in June 1901:

‘Dearest of Mams,

Here I am in the highest town in England. Robinson and I are exploring the moor over our Sherlock Holmes book. I think it will work out splendidly – indeed I have already done nearly half of it. Holmes is at his very best, and it is a very dramatic idea – which I owe to Robinson. We did 14 miles over the moor today and we are now pleasantly weary.’

Arthur Conan Doyle, writing to his mother from Princetown, June 1901.

Princetown (not the

highest town in England – that’s Flash in Derbyshire by 33 feet), is where Conan

Doyle and Fletcher Robinson took rooms at the Duchy Hotel in 1901 before their

exploration of the moor. In 1941 the hotel became the Dartmoor Prison Officers’

Mess, and remained so until the early 1990s when it became, and remains, the

Dartmoor National Park High Moorland Visitor Centre.

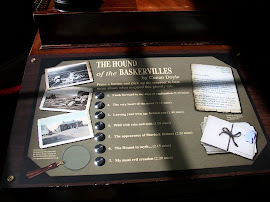

In this building

there is now a permanent Sherlock Holmes exhibition, including a life-size

mannequin of Holmes and the Hound, and a full-size portrait of Conan-Doyle watching his famous

creation going out onto the Moor, as well as other exhibits. I also purchased a 'Hound of the Baskervilles Trail' leaflet.

Nearby is Fox Tor Mires, the most likely candidate for the ‘Great Grimpen Mire’, which I visited on my last Dartmoor trip.

My final stop of the day was at Dartmoor Prison, founded in 1806. The prison was originally used to house French and American prisoners of war captured during the Naploeonic wars until 1816. The prison was re-opened in 1850 when England’s jail population was reaching a peak. On 13th June 1901, as Conan Doyle was completing the third instalment of ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ two convicts named William Silvester and Fergus Frith made a widely publicised escape. This almost certainly inspired the escape of Selden the Notting Hill Murderer from ‘Princetown Prison’ in ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’. The prison now features a museum that I visited.

Catching two buses, first to Yelverton (close to the stables from ‘Silver Blaze’), and then to Plymouth, I made my way back to my room to collapse exhausted.

Go to Part Two